Faculty Perspectives: Student Course Feedback

1. Introduction

Student feedback on courses is an important component in evaluating the quality and effectiveness of the course. In addition to providing useful input from a major stakeholder in the learning process, course evaluations also provide a moment of reflection for both instructors and students, and provide an avenue for these stakeholders to improve the course for themselves and future students. Course evaluations are often administered at the end of the semester but can also be offered at any other time when feedback from students might prove insightful.

It is often helpful to frame student feedback, and the mechanisms for collecting said feedback in a more formal context, i.e. what is the research question, how will this question be answered and evidenced, and, how will the resulting data then be reported to the relevant stakeholders or otherwise utilized. An effective feedback mechanism will have a specific set of questions in mind and use targeted activities that are appropriate to answering these questions.

1.1 Mid Semester Feedback

Mid Semester Feedback is most often formative in nature as it allows instructors to gain information about their course that can be used to make more immediate improvements and changes that affect the currently enrolled students.

1.2 End of Semester Feedback

End of semester feedback is often summative in nature and evaluates the course as a whole. It can, however, be viewed as a formative evaluation that can be used to develop future versions of the course and can build on ideas generated in mid semester feedback.

2. Collecting

Prior to obtaining feedback it is important to consider who, what, when, and how data will be collected. First identify who feedback will be solicited from, including class size and characteristics. Determine what data will provide the most meaningful picture of the course experience. Feedback questions can be framed to align with course objectives or professional practice standards, identify engaging teaching modalities, and enhance student reflection. Formative data may include feedback regarding what should start, stop, or continue to be done in a course. This data can also be utilized summatively to modify a course for future semesters.

When to obtain student feedback is dependent on the underlying aim of data collection. Consider the timing, length, and frequency of feedback requests, particularly to avoid survey fatigue. Mid semester feedback is often formative and collected half way through the course, whereas end of semester feedback is summative and collected during the final weeks of the course. Feedback requests should remain available to students for at least one week. To increase participation, feedback may also be requested during synchronous class time.

How to collect data is a key aspect of obtaining useful student feedback. Here are some key things to consider as you prepare to collect data:

- Be mindful of specific department policies related to required or expected data collection. Does your department have required survey questions? Does your department expect you to use an online platform to collect data?

- When conducting a survey, the response rate of the survey should be collected and noted in your discussion and documentation.

- Consider the use of open ended versus targeted questions. Open-ended questions provide qualitative data for thematic analysis whereas targeted questions can more easily generate quantitative data that can be analyzed for common patterns and relationships such as: mean, median, mode, and standard deviation.

Focus groups are another modality of data collection that can provide qualitative data for analysis. Anecdotal evidence can also be collected through maintaining data from student emails and comments.

3. Analyzing

Depending on the type of data which were collected, analysis may be more qualitative, quantitative or a combination of the two. Before analysis however, it is important to de-identify any data that has been collected, if it was not already anonymized at the point of data collection. Collecting anonymous data gives students more freedom to express any (hopefully constructive) criticisms of the class as well as removing any bias the instructor might have towards certain students.

Quantitative data is comparatively easier to work with than qualitative data but unless it is well targeted and the research questions are well developed, it is often harder to derive meaningful feedback using this approach. Best practices in terms of collecting and analyzing qualitative course data can be found in the references section below.

No matter what kind of feedback is developed as part of the course, it is generally a good idea to analyze the data for themes and patterns in responses. While the feedback of a single participant might be useful, aggregated data is often more indicative of the general perception of the class. As much of the data received from student feedback is qualitative, it is likely that this data will need to be coded or condensed to elicit these themes in responses. Trends which may be of particular interest include the progression or changes from mid to end of semester, or from semester to semester. This is also a way to examine and track any changes in student performance or course experiences resulting from pedagogical changes which have been made. It can often be useful to develop a narrative based on the course feedback and changes made to the class that resulted from this feedback. Writing the feedback into a narrative forces the instructor to reflect on the course and what they may, or have changed, and can be useful in other circumstances beyond simply improving the given course, for example in preparing a teaching dossier or similar.

Finally, for courses consistently taught over time, improvements in feedback and evaluations can also be examined between important timepoints such as from the 2 year to 4 year review – assuming that the same, or similar data has been collected, and that it can be compared over various timeframes.

4. Representing & Reflecting

When deciding how best to represent and reflect student feedback data it is important to think about the target audience. The following will focus on documentation and representation of student feedback in the dossier, such as including a summary of the data over time for purposes such as promotion and tenure.

4.1 Display Options and Examples

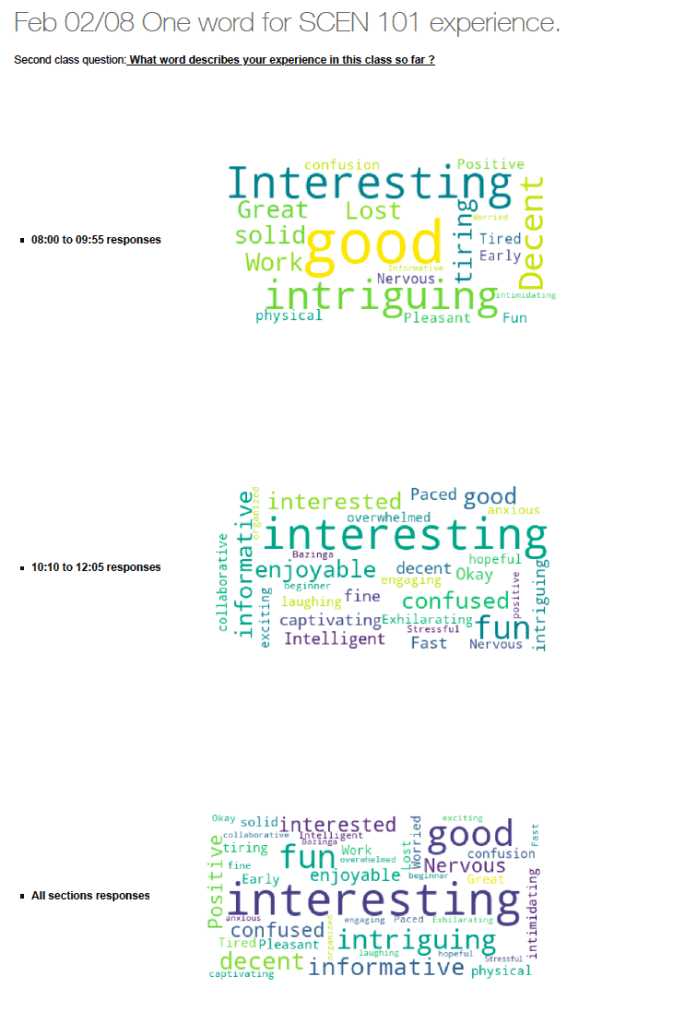

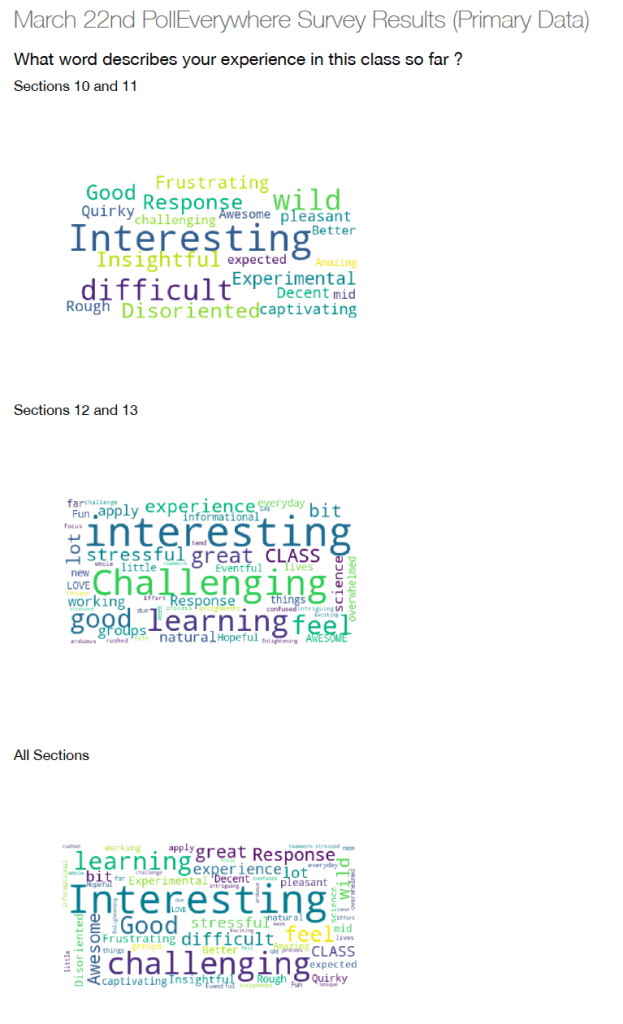

Adebanjo Oriade, Department of Physics and Astronomy, shares his use of word clouds for documentation here.

- Word Clouds for visualizing text feedback from students. Works best with one word responses.

- Word Clouds give a quick global, objective view of how students are doing and feeling. Word clouds can save the instructor from individual responses that might be negative triggers. Feedback perceived as negative can halt the process of reviewing student feedback. Such individual or local views lead to subjective analysis. A word cloud shows a bigger picture and highlights scale. How important or dominant is a particular sentiment?

- In an Introductory Physical Science class, during the second class of the semester I asked students, “What word describes your experience in this class so far?” I asked the same question a few weeks later in the semester. This was after the first exam and the first major group project was completed. The word clouds created from feedback each time the poll was taken is shared below. It was shared with students on a Canvas page each time. The instructional team used all themes featured in the word clouds to celebrate work and identify areas for improvement. The words “interesting”, “good”, “great” were major themes in the word cloud, this suggests the instructional team is doing something right.

- Note: If the word “not” is ignored by the program, one can be led to a wrong conclusion, so check sample feedback.

- Words like “Lost”, “Challenging”, “overwhelmed”, “Frustrating”, “Disoriented” encourage the instructional team to ask questions like “How can we make your learning less _______ ?” Student responses to these questions guide follow up action to improve student learning experiences.

- Without the word cloud, it is hard to get a better sense of proportions. Word clouds can also be used for longer responses, such as to Start-Stop-Continue queries. For meaningful analysis of longer responses the word cloud is only a starting point. Instead of reading through fifty pages of feedback from a large class, and instead of picking feedback randomly the word cloud can guide selection of a manageable sample size to review.

Charts and tables are a popular option for organization of student feedback. This option allows for ongoing storage of data and can also be a beneficial tool for displaying themes in student evaluation data and instructor reflection (see example template).

Table X: Example template for collating student feedback data and reflections.

| Course # | Course Title | Semester | Credits | Eval response rate | Eval Course Mean | Eval Instructor Mean | End of Semester Feedback | Future Course Adjustments |

Qualitative data such as representative student quotes can be collected from both course evaluations as well as from unsolicited student communications such as emails. These do not need to be limited to only the most positive student comments. Constructive student comments can also be an opportunity for reflection on course design as well as an opportunity to demonstrate the way in which student feedback has influenced course changes and revisions. This demonstrates a responsive instructor and shows both students and reviewers the ways in which student feedback is utilized to improve the student experience and course delivery. Including a mechanism for mid-course feedback from students may support more productive end of course feedback as minor problems can be identified and addressed earlier on in the class, and responsive instructors who share their mid-course feedback data can in turn help students to feel more confident that their feedback is being utilized to improve the course and thereby be more invested in providing thoughtful end of course evaluation feedback.

4.2 Reflecting on Feedback

Reflection is a critical learning strategy that can be part of the course feedback experience for both students and instructors. For students, mid or end of semester feedback can represent an opportunity to reflect on the course in various, beneficial ways. For instructors, considering student feedback is an essential part of reflective teaching. This type of reflection supports effective and student centered teaching, and is facilitated by instructors evaluating their teaching practice including instructional design choices and any necessary revisions to improve aspects of student belonging and learning.

One way that educators can utilize self-reflection in their teaching practices is by asking for feedback from students at different points throughout the semester. According to Medina et. al (2019), “gathering student perceptions of teaching and course delivery is important because students are the direct recipients of the instruction and can offer important insights regarding the learning and assessment process and how teaching can be improved” (p.1). Traditionally, course evaluations are completed at the end of the semester, but the authors suggest a model that includes more continuous feedback in order to make improvements to their courses in “real time.” This allows for important formative feedback for the instructor as well as increased investment and engagement for the students.

Representative student comments from various course evaluations and feedback can be documented in the teaching dossier as a narrative or table, and then the instructor’s reflections on and response to the student feedback can and should be included also. This includes additional context which may help to better interpret and represent the feedback, as well as the instructor’s plans for any improvements on the course based on the feedback obtained. Ideally, for a course taught over several semesters, this type of chart would show the growth and development of the course with examples of student feedback which influenced that development as well as feedback as evidence of the impact of those improvements in subsequent semesters. Additionally instructors can then incorporate in narrative form their own reflections on their growth and development in teaching effectiveness over time.

References & Further Reading

Center for Teaching and Assessment of Learning. (n.d.). Mid-course feedback. University of Delaware. https://ctal.udel.edu/resources-2/mid-course-feedback/

Fass-Holmes, B. (2022). Survey fatigue- What is its role in undergraduates’ survey participation and response rates.Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education, 11 (1), 56-73.

Hurney, C. A., Harris, N. L., Prins, S. C. B., & Kruck, S. E. (2014). The Impact of a Learner-Centered, Mid-Semester Course Evaluation on Students. Journal of Faculty Development, 28(3), 9.

Lewis, K. G. (2001). Using Midsemester Student Feedback and Responding to It. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2001(87), 33. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.26

Medina MS, Smith WT, Kolluru S, Sheaffer EA, DiVall M. A Review of Strategies for Designing, Administering, and Using Student Ratings of Instruction. Am J Pharm Educ. 2019 Jun;83(5):7177.

Wachtel, H. K. (1998). Student Evaluation of College Teaching Effectiveness: a brief review, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 23:2, 191-212, DOI:10.1080/0260293980230207

Yale Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Reflective teaching. https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/ReflectiveTeaching

https://www.scholarlyteacher.com/post/analyzing-student-end-of-course-written-comments